Management & Care of Offenders with Learning Disabilities

Management & Care of Offenders with Learning Disabilities

This workshop, run by The Butler Trust in association with The Prison Reform Trust, focused on the management and care of offenders with learning disabilities, both in custody and in the community.

This workshop, run by The Butler Trust in association with The Prison Reform Trust, focused on the management and care of offenders with learning disabilities, both in custody and in the community.

[For further examples of good practice in this area see the learning disability interest group on good-practice.net.]

A Word About Words

To some people the phrase ‘learning disabilities’ sounds like off-putting and unclear jargon. In fact, it’s just the latest in a long list of historical technical terms which once included cretin, imbecile, idiot, moron, retarded and mental handicap. As each term moves out of medical practice and into the mouths of playground bullies, so new terms get coined to take their place. Other current terms you might hear include ‘learning difficulties’, ‘intellectual disabilities’ and ‘mentally challenged’. Keeping up with the lastest jargon on this ‘euphemism treadmill’ might seem like punishment enough, but whatever the language used, the reality is no less pressing.

One common current technical definition of ‘learning disabilities’ is someone with an Intelligence Quotient (IQ) of 70 or below – someone with perhaps a third (or more) less intelligence at work than the average person.

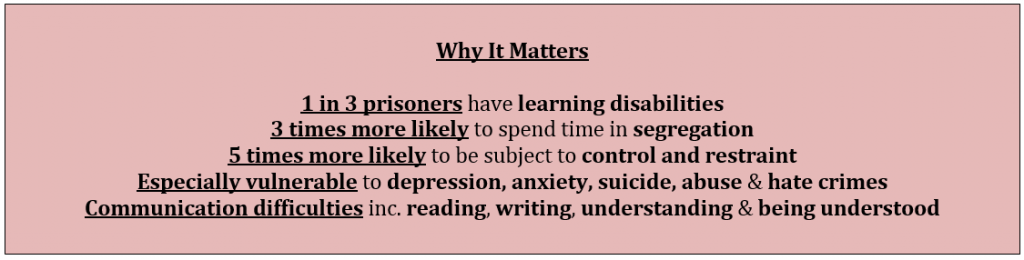

A third of prisoners have an IQ of 80 or less. Meanwhile about a quarter of child offenders have learning difficulties and around 60% have communication difficulties.

One Big Problem

Numbers aside, it can be difficult to imagine even a fraction of what living with learning disabilities means, and how that might feel while in custody, court, prison or a probation setting. These words give a clue…

The Presenters

Our opening presentation came from Jenny Talbot OBE of the Prison Reform Trust. Jenny joined the PRT in 2006 with a specific remit to look at the high prevalence of people with learning disabilities in the penal system – and five years later received an OBE for her work. She began with a short film produced by the PRT and KeyRing, a group working with vulnerable people in the community. Watching two former prisoners with learning disabilities describe their painful experiences made for powerful and moving viewing. As one ex-offender put it, “I didn’t even know that I was going to prison… I know there was something slightly wrong with me, but I didn’t know what.” (you can watch it here (you’ll need to scroll down the page)).

Jenny gave a comprehensive overview of the issues. These include, in particular, a host of communication-related problems. These range from not being able to read – whether words or other cues like body language – to difficulties simply understanding or remembering tasks. As well as being suggestible, people with learning disabilities are prone to depression and anxiety. Official recommendations include access to Liaison and Diversion services – in short, picking up and responding to the problem as quickly as possible. [view Jenny’s presentation]

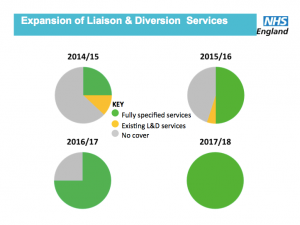

Kate Davies OBE, Head of Public Health, Armed Services and their Families, and Health & Justice at NHS England, took up the process theme with a comprehensive look at these relatively new Liaison and Diversion services including early identification, screening and assessment, and referrals.

Kate Davies OBE, Head of Public Health, Armed Services and their Families, and Health & Justice at NHS England, took up the process theme with a comprehensive look at these relatively new Liaison and Diversion services including early identification, screening and assessment, and referrals.

With a budget of £472 million and deployment across a wide array of partnerships, the new approach is being rolled out and expanded nationally over the next few years (see figure).

Kate noted that the United Kingdom is “one of the world leaders in quality of health care in the justice system”, and pointed out the increased risks for people with learning disabilities of suicide and hate crimes. [view Kate’s presentation]

The next speaker was a surprise: the kind of expert who is all too often an absent voice at workshops and conferences. Darron Heads held the audience spellbound as he made a short but powerful presentation. Darron is a member of the Keyring Working for Justice group.

Darron has learning disabilities himself – as well as extensive experience of the criminal justice system. He spoke with refreshing directness about simple practical measures, like making documents easy to read, and using digital clocks instead of analogue ones, which some people with learning disabilities struggle with. Darron ended with a rousing cry: “Get a life, not a service!”. [view Darron’s presentation]

For a deeper understanding of what an outstanding programme addressing learning disabilities in prison might look like in practice, we turned to 2013 Butler Trust Award Winner, Lisette Saunders from HMP/YOI Parc in South Wales. Lisette and her team use a 60 question computer test (including voice to get around reading problems) to identify and profile people with learning disabilities. This ‘profiler’ is used within the first 48 hours of induction, and the results inform a carefully mapped set of pathways, including a supported living plan toolkit and management plans. Results indicating high needs lead to case conferences involving specialist nurses and other team members.

The results are remarkable and a testament not only to the benefits of early, intelligent actions for often highly vulnerable people, but also the quality of some of the work going on in the system. The bullet points from her case study (see right) are both sobering and inspiring.

The results are remarkable and a testament not only to the benefits of early, intelligent actions for often highly vulnerable people, but also the quality of some of the work going on in the system. The bullet points from her case study (see right) are both sobering and inspiring.

It’s worth noting that one of the project’s founders, and the Deputy Governor, both had children with autism, giving them a greater level of awareness of and insight into the needs of people with learning disabilities. [view Lisette’s presentation]

Janet Lockhart from The Manchester College made the point that one of the key problems dealing with learning disabilities is that they’re often not visible. Understanding the complex range of such disabilities – from people on the autism spectrum to those with ‘attention deficit disorder’, and from dyslexia to illiteracy – is difficult enough for experts. How much more difficult is the task for officers who may not have any training or relevant experience?

She demonstrated that a combination of engagement and tenacity, working together with a hundred ‘inclusion champions’ could lead to major and measurable improvements in services delivered for those with learning disablities. Janet ended with an inspiring quotation: ‘When people are known for their gifts, their difficulties remain unknown. When people are known for their difficulties, then their gifts remain unknown’. [view Janet’s presentation]

Quite how complex the issues are was highlighted by the final speaker, Mick Pykett from Star Therapy (and previously a prison officer), whose specific expertise addresses sex offenders with learning disabilities. His presentation began with a quick summary of definitions, terminology, and some of the common ways in which ‘masking’ behaviour can be perceived as being rude or cheeky, unmotivated, or can look like a failure to respond well to instructions or treatment. He listed several psychological features:

- Fear of failure

- Sensitivity to disability

- Not confident to ask for help

- Frustration/give up easily

- Desire to please

- Masking

From reduced reasoning skills to various memory problems, Mick unpacked the range of problems and introduced an approach called VAK – Visual, Auditory and Kinaesthetic. The Visual concentrates on using posters, photos, pictures and so on as part of a move away from reliance on written material (and with simplified words and timelines). The Auditory focus is on short, simple questions, delivered one at a time, in simple language. Kinaesthetic elements might include moving around as part of a warm up exercise or role playing. [view Mick’s presentation]

Breakout and discussion

The Q&A and breakout sessions covered these issues, and more, in greater depth, with the discussion identifying that, while learning disabilities was firmly on the agenda at last, there was still a pressing need for greater levels of resource, training, assessment tools, and integrated treatment approaches. No one was under any illusions about the sheer complexity of building staff confidence to consistently address the prevalence of people with learning disabilities in the system, nor the urgent need to raise the awareness and profile of this pressing issue.

[For further examples of good practice in this area see the learning disability interest group on good-practice.net.]